Supercharging and Fuel Pressure

|

Regarding the fuel pressure...( From my experience...) Old technology: On Studebakers applications that used a Mcculloch VS series, you have to understand that the boost was designed to only be applied infrequently and for short periods of time (for acceleration). Their method of fuel pressure regulation was to connect the output pressure of the blower  The size of the carb jets, in all their supercharged applications, is larger than normal. This is so the engine receives a constant rich atmosphere, in all phases of operation, whether or not it's in a boosted condition. The static rich condition was required, so that when the boost came into play, the richer mixture cooled the charge with added fuel and prevented detonation, which would be caused by too lean a mixture. It provided a denser fuel charge for the denser atmosphere.

When you regulate fuel pressure, with a boost signal (from the supercharger output volute), it impacts the engine operation significantly. Because the blower drive ratio varies through the VS series front pulley and internal planetary drive gear, the opening and closing could cover a wide range of pressures. This was more critical in the early McCulloch (53-58) because the split pulley would open in a heartbeat, increasing the boost almost immediately, also raising the fuel pressure pressure considerably (and immediately). The slower increase of engine rpm can't use the maximum fuel pressure it's receiving right away, so what happens is a drawback of supercharging in this manner.

The Avanti application was a bit different because of the constant blower / crankshaft speed ratio. This setup still had the rich jetting, but at highway speeds, the blower pressure was kept in play, moreso. The fuel pressure compensation was still needed, as were the drawbacks of over pressure and in their attempt to solve other non-related problems, cured or rectified some of the boost condition ones. The Avanti has known under hood temperature problems, which produces a problem called fuel perclolation. This occurs when fuel is kept standing in a line (by the action of the needle and seat in the carb) and being close to a high temperature point, results in the fuel boiling, thus displacing fuel with pockets of vapor ( vapor-lock) and starving the engine until it stalled (embarrasing moment).

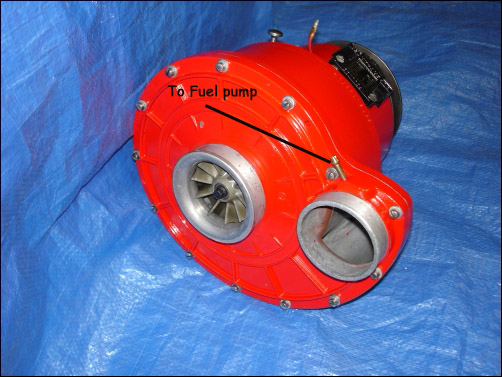

What wound up countering this problem is one thing that was either, thought of by the engineers or just fell into place because of another. The engineers added a return fuel line to the gas tank that originated at, the carburator So the action of Paxton style blower, when you stepped in it, was a smoother increase of power, with a considerable decrease to the black trail, from the exhaust. There was still the flapper valve on the R2 to vent gas which puddled on the stove under the carb inside the intake manifold and the carb was sealed to prevent fuel from blowing out onto the engine. The R3 only had the flapper, as far as I know, and the carb doesn't need to be sealed because the boost pressure is external to the carb, like the 57-58 Golden Hawks. Some of the early Avanti II's still had the return line. Later ones had it removed, although the fitting on the tank is still there, but soldered closed. New technology: I've owned a 57 GH and a 64 R2, so when I decided to supercharge my current 1970 A-II, I went through all the machinations of attempting to replicate the Studebaker engineering. I labored to make a fuel pump with a fitting on the upper casting. That didn't work too well on a Chevy pump, so an old Hot Rod issue had what I thought was needed. Their article on supercharging a 'modern' car with a Paxton, had the solution as being " route the fuel from the pump to a Holley FP regulator. Then modify the regulator to emulate the top of the Stude type fuel pump". So I purchased a Holley Blue which came with their FP regulator and modified it as described. This worked somewhat, but in too many situations, the fuel pressure would overcome the regulator and flood the carb, resulting in more embarrasing situations... My complaints to Holley went unanswered. What I finally came up with was kind of like a "Studebaker" solution. I fabricated a return fuel line to the fuel supply. Remember, I had an electric fuel pump ( mounted inside the passenger side front hog trough outrigger), so the return merely had to be routed to the line supplying the pump, not all the way to the tank. Then I purchased a Mallory 4309 regulator, which has 4 ports. port 1 is the supply, 2 is to the carb, put an electric fuel pressure sender in the third and routed the 4th back to the pump input fuel line. This works very nicely. The carb is an Edelbrock with a rod size increase to provide the static enrichment at both cruise and power. I bolted an R3 airbox to an Edelbrock Performer manifold. The blower was made for me by John Erb with a tighter pressure spring pack and high output impeller. My engine is a Jasper Class II 350/330 Hp before supercharging (8:75 compression). Must put out around 450HP at full chat. I gave Lionel Stone the specs of all my work and now he's selling Avanti II Paxton kits, but all the design stuff is on my website anyway. The only other way to apply a blower these days is to use a 1996 or later chassis with OBDII diagnostic connector and tweak the injection system with a laptop/software. You might have to buy a performance processor chip to achieve the best output. This type system would alleviate the extra rich condition required by mechanical components.

Bob Johnstone |