I called Bob, and he confirmed—a pale yellow Avanti, 1970, 350 engine. The car was moved to Washington state (where he lives), he sold it “about 20 years ago ,to a man in Spokane WA.” He sent me pics of the car at that time (see attached).

I looked through several AOAI member “yearbooks” (back to 1998, anyway), but nothing matched this description. Then I looked on your site: specifically at RQB-1585 (“RQB-1585 - Spokane, WA, June 2005…”) This certainly matches the description!

Just to get some hard evidence, I contacted Dan Booth to see if he could find any build sheet with the name Adrian Marks. I also let him know that RQB-1585 might be the car. Once he looked, he said that RQB-1585 was sold to “Matt Smith Motors”… in Frankfort, IN. This is the town that Adrian lived! Also, the build sheet indicates, “Special Paint exterior… Kashmir Ivory… Trim …Colonial Yellow vinyl , paint…”). I can send this to you, if interested.

So! It’s circumstantial evidence I know, but it’s close. Without that title from MSMotors to Adrain, we may never know for sure. But without a doubt, Adrian Marks owned an Avanti.

Now, where do we go from here? “RQB-1585, presumably owned by Adrian Marks, WWII pilot who first landed and rescued survivors from the USS Indianapolis…” I would be glad to put something together, but I didn’t know how involved to get. I could write a small article, as a matter of fact—ha! But he owned an Avanti, to be sure!

Joe L.

Adrian Marks was born in Ladoga, Indiana on February 18, 1917. He was a graduate of Northwestern University and earned a law degree from Indiana University. His father was also a lawyer. He joined the Navy prior to the United States entry in World War II.

NY Times, 15 March 1998

Adrian Marks, 81, War Pilot Who Led Rescue of 56, Is Dead By RICHARD GOLDSTEINMARCH 15, 1998 Adrian Marks, a Navy pilot who rescued 56 sailors struggling in the shark-filled Philippine Sea after the cruiser Indianapolis was sunk by Japanese torpedoes in July 1945, died on March 7 at Clinton County Hospital in his hometown of Frankfort, Ind. He was 81.

Lieutenant Marks was flying a seaplane designed for landings only in calm water. He had been ordered never to touch down on the high seas. But on what he would remember as ''a sun-swept afternoon of horror,'' he disregarded his orders, risking his life and the lives of his eight crewmen, and began a dramatic mass rescue following the worst disaster at sea in American naval history. The attack took almost 900 lives.

Lieutenant Marks later had the Air Medal pinned on him by Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet.

The Indianapolis, unescorted and carrying 1,200 men, was en route to the Philippines from Guam, having delivered atomic-bomb components to Tinian, when it was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-58 around midnight of Sunday, July 29.

The submarine skipper, Lieut. Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto, ordered the firing of six torpedoes; two struck the Indianapolis. Rocked by the explosions, she rolled over and sank in 12 minutes. Some 400 men were lost outright, but 800 others scrambled into the water as S O S's were radioed.

No one ever heard the distress calls, so far as is known. And because of slip-ups and bureaucratic lapses, Navy commanders would not think to look for the Indianapolis even when it became officially overdue at Leyte Gulf, the Philippines.

All through Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, the survivors of the torpedo attack -- suffering from injuries, sunburn and dehydration and menaced by sharks -- thrashed about in the sea. By Thursday, Aug. 2, only 320 of the men were still alive. Then, at about 10 A.M., a Navy pilot flying a routine mission spotted figures bobbing in the water.

Lieutenant Marks, summoned from the island of Peleliu, piloted the first rescue plane to arrive. He dropped three life rafts in the late afternoon, but one broke up when it hit the water. He then polled his crew members about whether they should make a dangerous open-sea landing that was forbidden by regulations. When they agreed, he set down his PBY5A Catalina plane, known as a Dumbo, amid 12-foot swells. The plane bounced 15 feet in the air after hitting the waves, but incurred only slight damage.

Speaking at a reunion of Indianapolis survivors exactly 30 years later, he remembered his crew members' realization that they could not rescue everyone. ''We would have to make heartbreaking decisions,'' he recalled.

''I decided that the men in groups stood the best chance of survival,'' Lieutenant Marks said. ''They could look after one another, could splash and scare away the sharks and could lend one another moral support and encouragement.''

Lieutenant Marks's crewmen first picked up the men who were alone, throwing life rings attached to ropes to the men. Soon there were two survivors in each bunk on the plane, and then men were lying two and three deep in all the compartments. Lieutenant Marks later shut off the engines and put additional survivors on the bobbing wings, tying the last of the 56 men down with parachute material.

And then night came. ''Even though we were near the equator, the wind whipped up,'' he remembered. ''We had long since dispensed the last drop of water, and scores of badly injured men were softly crying with thirst and with pain. And then, far out on the horizon, there was a light.''

It was the destroyer Cecil J. Doyle, the first of seven rescue ships that were belatedly dispatched.

The survivors were hauled onto the Doyle, followed by Lieutenant Marks and his crewmen, and the Doyle and other ships later fished others out of the water. The next morning, the Doyle sank Lieutenant Marks's plane, now too damaged to fly again.

Twelve days later, Japan surrendered, ending World War II.

The skipper of the Indianapolis, Capt. Charles B. McVay 3d, was court-martialed in December 1945 and found to have left his ship vulnerable to torpedoes by maintaining a straight course rather than zigzagging. He was allowed to remain on duty, but his career was ruined. Reprimands were issued to four officers in the Pacific over the failure to mount a timely rescue operation, but these were later rescinded.

Robert Adrian Marks (he did not use his first name), a native of Ladoga, Ind., and the son of a lawyer, had graduated from Northwestern University and Indiana University Law School before the war. He was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on Dec. 7, 1941. He later attended flight school, became a pilot and served as an instructor at the Pensacola, Fla., naval air station before going to the Pacific. After the war, he returned to his Frankfort home -- some 40 miles from Indianapolis -- and opened a law practice, specializing in real-estate titles and deeds.

He is survived by his wife, Elta; a son, Robert, of Bellevue, Wash; three daughters, Pamela Levine of Lakeville, Mass., Alexis Shuman of Enumclaw, Wash., and Lynn Larson of Olympia, Wash; a foster son, John Barlas of Mercer Island, Wash., and 10 grandchildren.

Over the years, Mr. Marks never let the events of Aug. 2, 1945, leave him.

Speaking at the 1975 survivors' reunion, he paid tribute to the sailors he rescued and to all others who had undergone a shattering ordeal.

''I met you 30 years ago,'' he said. ''I met you on a sparkling, sun-swept afternoon of horror. I have known you through a balmy tropic night of fear. I will never forget you.

Journal Review 02 Aug 2015

Remembering A Hero

Adrian Marks saved 56 sailors stranded at sea 70 years ago

Bob Cox bcox@jrpress.com Aug 2, 2015

War Hero Marks

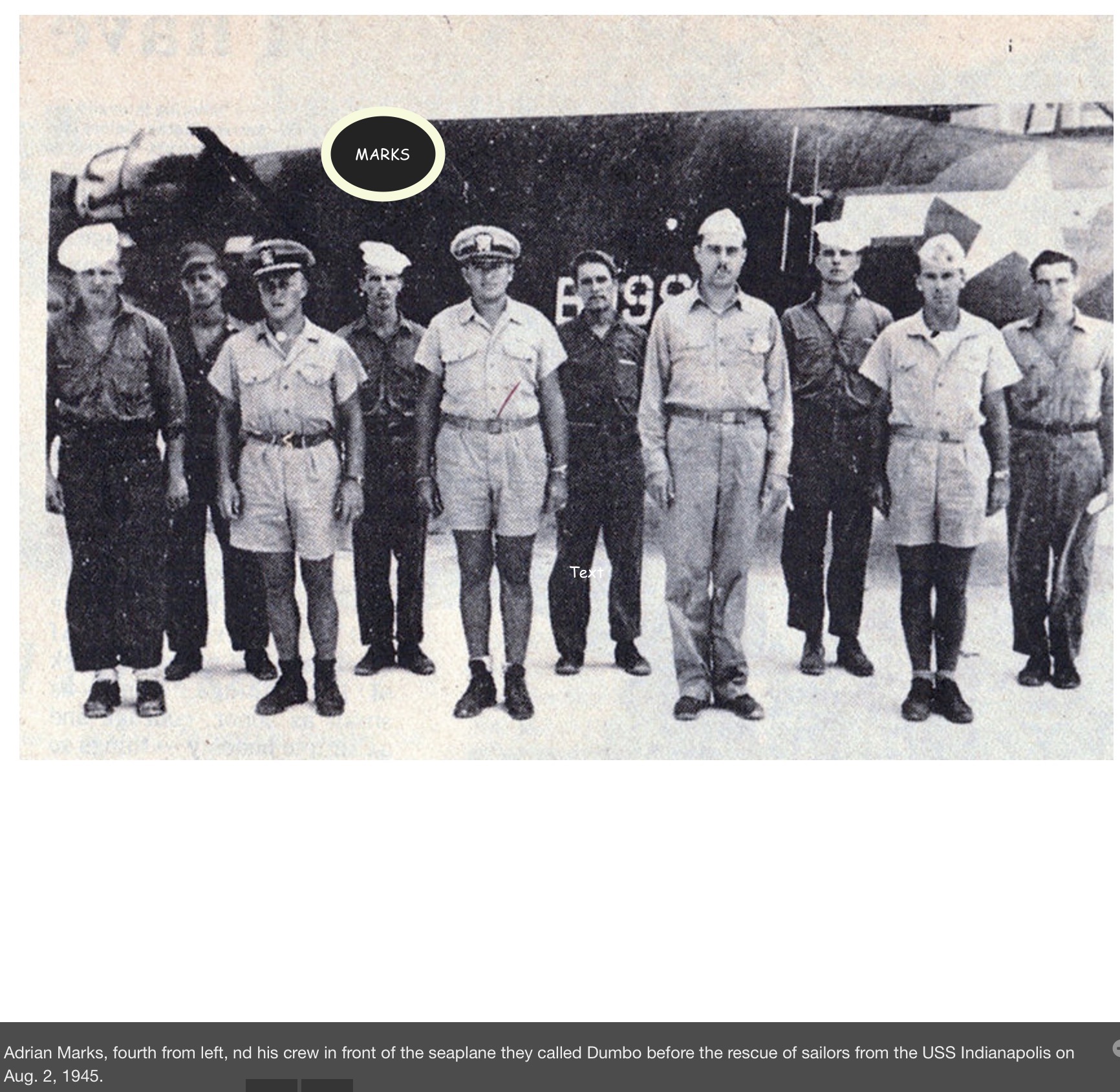

Adrian Marks,  fourth from left , and his crew on Aug. 2, 1945, in front of the seaplane they called Dumbo before the rescue of sailors from the USS Indianapolis

fourth from left , and his crew on Aug. 2, 1945, in front of the seaplane they called Dumbo before the rescue of sailors from the USS Indianapolis

Thursday marked the 70th anniversary of the largest loss of life in a single attack of a U.S. naval ship. More than 900 men and women died when the USS Indianapolis was destroyed by two Japanese torpedoes while en route to the Philippines from Guam. The loss of life would have been more without the heroic efforts of Adrian Marks. The Ladoga native risked his life to save others in the shark infested waters Aug. 2, 1945.

On July 30, 1945, a Japanese submarine spotted the USS Indianapolis and fired six torpedoes at the unescorted battleship. Two struck the Indianapolis. The ship rolled over and sank in 12 minutes. Some 300 sailors died immediately and nearly 900 scrambled into the water. The ship went down so fast few lifeboats could be put into the water that Sunday evening.

All through Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday the men were left bobbing in the sea because S.O.S. signals were never received by U.S. Navy officials. No one was aware the ship had sunk. Sharks started attacking survivors Monday evening. By Thursday, Aug. 2, only 320 men were still alive. Finally, at 10 a.m., a Navy pilot flying a routine mission spotted the men bobbing in the water.

Marks was ordered to fly his rescue plane to the scene. He dropped rescue rafts and then made a dangerous but heroic decision. He set down his PBY5A Catalina plane amongst the 12-foot waves which caused the plane to bounce 15 feet into the air after hitting the waves. The plane was damaged but still stayed afloat. The open sea landing broke Navy regulations but Marks said at a reunion of Indianapolis survivors 30 years later, it was the right thing to do. Even after landing Marks knew he would not be able to rescue all of the men.

“We would have to make heartbreaking decisions,” Marks said. “I decided that the men in groups stood the best chance of survival.”

Mark’s crewmen first picked up the men who were alone. Soon men were lying three deep in all the plane compartments. Later Marks would shut down the engines and put additional men on the plane’s wings, tying the last of the 56 men down with parachute material.

Night soon was upon the rescue team as the plane bobbed up and down. Marks talked about facing the perils of the sea at night.

“Even though we were near the equator, the wind swept us,” Marks added. “I had long dispensed all of our water, and scores of badly injured men were softly crying with thirst and pain. And then, far out on the horizon, there was a light.”

It was the destroyer Cecil J. Boyer, the first of seven rescue ships that were dispatched.

The next morning Marks’ plane, which was too damaged to fly again, was sunk by the Doyle.

Lifelong Ladoga resident, Chet Vice, remembers Marks as an intelligent student. When Marks was a senior at Ladoga High School, Vice was a freshman in 1937.

“Adrian Marks was one of the smartest guys I ever knew,” Vice said. “He was kind of a loner, but he grew up in a nice family. His father was an attorney in Ladoga at the time.”

Marks, who graduated from Ladoga High School with former long-time Crawfordsville attorney Beecher Young, went on to graduate from Northwestern University and Indiana University Law School before the war. He was stationed at Pearl Harbor when Japan attacked the U.S. Naval Fleet on Dec. 7, 1941. He later attended flight school, became a pilot and was a flight instructor in Florida before going to the Pacific.

Before Marks left the Navy, he had the Air Medal presented to him by Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, the commander of the Pacific Fleet.

After the war Marks returned to Ladoga but, like many returning veterans, never talked about his heroism. Vice, who is 97, was not aware Marks was a hero until several decades later.

“I do not think anyone in Ladoga ever realized what Adrian had done,” Vice said. “It was not until many years did we start to realize how big of a deal it was.”

Vice said the last time he remembers seeing Marks was at the town’s Sesquicentennial Celebration in 1986. Marks was in the town’s parade, quietly driving an antique car.

After the war Marks owned a successful abstract company in Frankfort, where he is buried following his death March 7, 1998.

Marks might have best described the day he landed his rescue plane while speaking at the 1975 survivors reunion when he paid tribute to the sailors.

“I met you 30 years ago,” he said. “I met you on a sparkling, sun-swept afternoon of horror. I have known you through the balmy tropic night of fear. I will never forget you.”

Today, Ladoga and Montgomery County should pledge to never forget Lieutenant Adrian Marks.

Military.COM

Military.com | by Bethanne Kelly Patrick As Lt. Adrian Marks gazed out of his PBY5A Catalina seaplane (also known as a "Dumbo"), he was stunned by the number of men in the water below. Bodies bobbed up and down, each movement revealing heads covered in oil and eyes glazed with dehydration and exposure -- eyes too dulled to care about the sharks picking off men at random. These were the remaining survivors of the USS Indianapolis, the cruiser whose wreck is the worst sea disaster in U.S. naval history.

The Indianapolis had delivered the world's first operational atomic bomb to the island of Tinian on July 26, 1945, and was then ordered to the Philippines for training. With his ship unescorted and carrying 1,200 men, ship's Capt. Charles McVay III opted, as was his prerogative, against a safe zigzag course. Instead, he chose the straightest and quickest route to Leyte Gulf. Just past midnight on July 30, the Indianapolis was hit by two Japanese torpedoes from Lt. Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto's I-58 submarine. Rocked by explosions, the U.S. ship sank in 12 minutes. Of Indianapolis' crew, 800 men scrambled into the water. Through a series of bureaucratic snafus, the ship was not reported as missing.

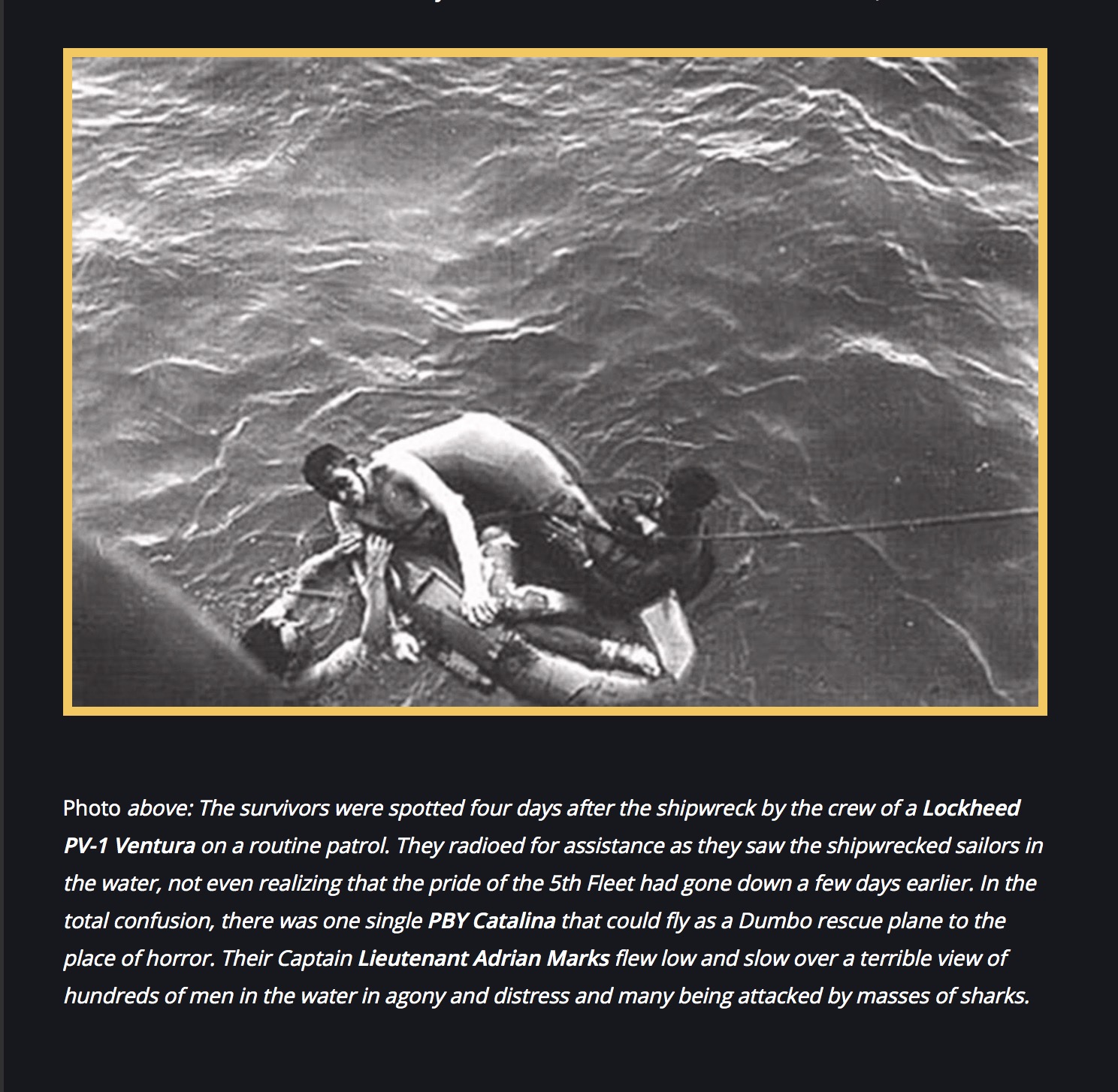

By the time Marks spotted them in the water on Thursday, Aug. 2, only 320 men remained alive. Marks' crew threw out life rafts and shipwreck kits, but the survivors were too weak to reach them. Marks immediately radioed for help, but knew he had to do what he could to save as many men as possible. He had been ordered not to attempt open-sea landings, but he also knew that no one could have foreseen the present situation. After polling his crew, all of whom assented to the landing attempt, Marks set down the Dumbo amid 12-foot swells.

"When we landed, we realized that we couldn't rescue everyone," he later recalled. "We would have to make heartbreaking decisions." The crew first rescued men who were alone. "I decided that the men in groups stood the best chance of survival," Marks said.

The heroic crew pulled survivor after survivor aboard the seaplane, placing the men two and three deep in all available compartments and, when those were full, tying them to the wings with parachute cord. All in all, Marks and his men rescued 56 near-wraiths from the sea. As night fell, a light appeared on the horizon: the destroyer Cecil J. Doyle, the first of seven belatedly dispatched rescue ships.

Marks, already a lawyer and an Indiana native, retired after the war to his Frankfort, Ind., home and opened a law practice. But he never forgot the men he had first seen from his seaplane. "I met you 30 years ago," he later told a reunion of Indianapolis survivors. "I met you on a sparkling, sun-swept afternoon of horror. I have known you through a balmy tropic night of fear. I will never forget you."

The Dakota Hunter

In a strange twist of fate, the supplying ship of the atomic explosives that indirectly inflicted the Empire’s final doom, that same USS Indianapolis would very soon after its deadly delivery come to grief by only 2 Japanese torpedoes. In a matter of only 12 minutes, the mighty ship was ripped apart by the second torpedo that hit amidships and ignited the ammo depots and fuel tanks. The ship was deadly wounded and capsized almost instantly, dragging some 300 sailors trapped inside into the abyss of the ocean. The battleship was halfway on its intended itinerary from Tinian to the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines.

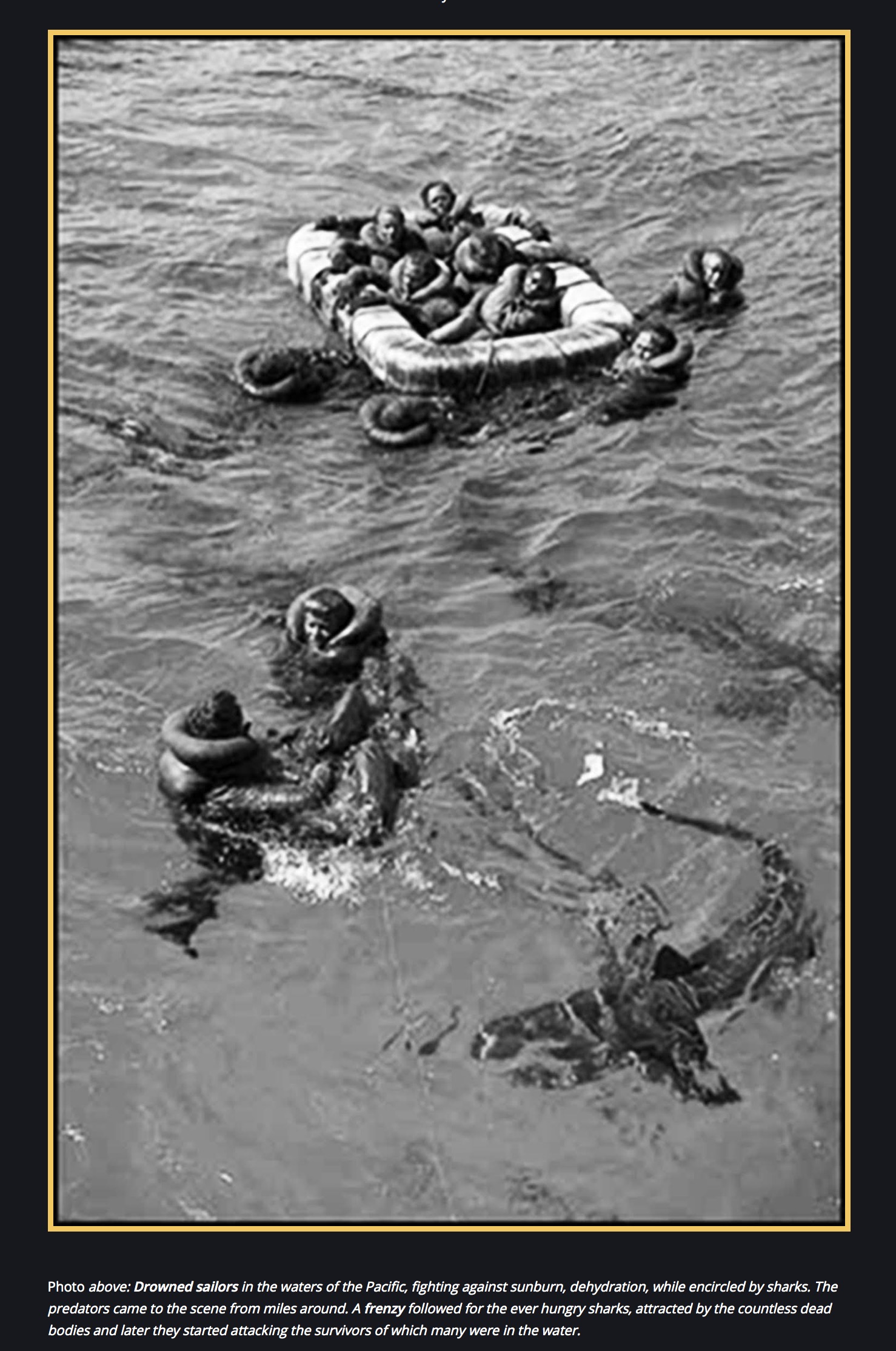

Of the total crew of 1198 sailors, some 900 survivors seemed lucky to have surfaced. They found themselves adrift in the open ocean. But there followed a second carnage: 3 days later, with all survivors left helpless in the water and no rescue operation deployed, only 317 sailors had survived the shipwreck’s catastrophe.

What went so terribly wrong that such could happen, hundreds of initial survivors of the Flagship of the Pacific fleet left unattended for almost 4 days on an open ocean?

Was it just very bad luck that the Jap Submarine ran into the USS Indianapolis? Or was the ship’s fate more or less “challenged” by poor precautions? Some serious doubts remained over why such disaster could have happened and when it happened, why was it that no distress message could be transmitted by radio for help. It was a tragic loss, the Navy learned from the mistakes made and implemented changes that improved requirements for procedures of radio silence, positions, ship escorts, and lifesaving equipment. In the investigation and court martial that followed, such flaws came to light. The most important conclusions were about the questions why the ship was unescorted, while that was against strict procedures of that time.

The USS Indianapolis did not have any sonar to detect submarines. The captain, Charles McVay, had asked for an escort before he sailed out, but his request was rejected. The US Navy also failed to pass on information that Japanese submarines were still known to be active in the area. The ship was all alone in the Pacific Ocean when it sank, the precaution taken of maintaining full radio silence was to the detriment in the rescue operation as no one knew the ship’s exact position. (For more information about this disaster, you can find information all over the Internet)

Lieutenant Adrian Marks took a very courageous decision and against all orders landed the PBY on the open ocean. He set his Catalina down amid 12-foot swells. While carefully taxiing the Cat, the crew started picking up the wounded and stragglers from the shark infested water. They surely were at the end of their forces and the effort to get them inside the aircraft via the small side hatch or the higher positioned waist blisters must have been immense for both the crew and the exhausted sailors. This rescue operation carried on for the rest of the day and only after midnight the destroyer USS Cecil J. Doyle arrived on the scene, followed by other ships, all helping to pull the final survivors out of the water. Estimates of the number who died from shark attacks range from a few dozen to almost 150. Whatever the score of the shark’s frenzy, the ordeal of the Indianapolis survivors remains one of the worst maritime disasters in U.S. naval history.

The PBY Catalina landed like an Ark sent by God but took some damage due to the high swell that threw up the Cat, bouncing over the waves. Marks was able to pull a total of 56 drowned sailors out of the water and later shut off the engines and put additional survivors on the bobbing wings, tying the last of the 56 men down with parachute lines. But with the cramped fuselage interior in mind, the majority of the rescued men were to be located on top of the main wing. With a wingspan of over 30 m./ 100 ft, this is not a small area and can house easily 40 people in quiet conditions. But wobbling on an ocean swell, with people that had spent 4 days in terror, things are way different. With all the stress that surrounded this rescue operation, with chaotic scenes of people screaming for help and trying to escape the shark’s attacks, this must have been a nightmare to get the people out from the water and from the fuselage interior on that pylon mounted wing. Imagine, access to the main wing is restricted to climbing out via the overhead hatches located above the pilot’s seats. Open this hatch and you can walk over the slippery fuselage top to the wing’s leading edge. There is a step in the front of the pylon that eases the entry to the wing, some 3-4 feet higher up. But there is no hand rail, so not a simple step to make for exhausted and disoriented men standing on top of a rocking ‘boat.

Read here the interview with one of the survivors, Lowell Dean Cox in his interview with the BBC World Service program:

“The sharks would come up and bump you. I was bumped a few times, you never know when they are going to attack you.”

“Some of the men would pound the water, kick and yell when the sharks attacked. Most decided that sticking together in a group was their best defense. But with each attack, the clouds of blood in the water, the screaming, the splashing, more sharks would come”.

“In that clear water, you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down. One came up and took the sailor next to me. It was just somebody screaming, yelling or getting bit.”

“The sharks, though, were not the main killer. Under the scorching sun, day after day, without any food or water for days, men were dying from exposure or dehydration. Their lifejackets waterlogged, many became exhausted and drowned. You could barely keep your face out of the water. The life preserver had blisters on my shoulders, blisters on top of blisters. It was so hot we would pray for dark, and when it got dark we would pray for daylight because it would get so cold, our teeth would chatter.”